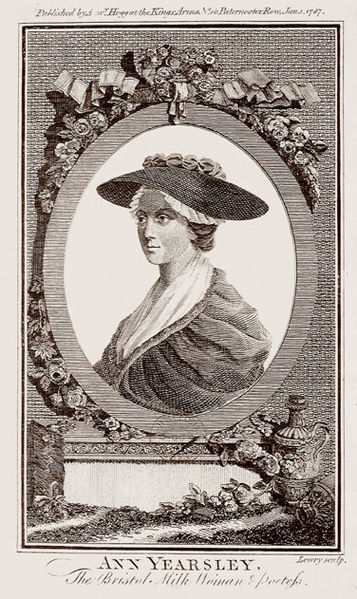

The English poet Ann Yearsley (neé Cromartie) died 215 years ago in May 1806. She was one of only a few working-class women of the time to gain distinction as a writer. Born in the 1750s, she was educated by her brother at home in Clifton and, according to one source, had access to books from a circulating library (Bristol’s first circulating library opened in 1728) though it is more likely that she received books borrowed from her mother’s employer. In 1774 Ann married John Yearsley, an unsuccessful farm labourer. Ten years later in 1784, at the end of a brutal winter, she was found by a benevolent gentleman destitute in a stable in Clifton with her husband, four surviving children (she was pregnant with her sixth) and a mother dying of starvation. After the birth of her sixth child, she took up the trade of milkwoman, selling milk door to door in Bristol, an occupation to which she has hereafter been synonymous.

@ National Portrait Gallery, London

Around this time she came to the attention of the poet, playright, bluestocking and philanthropist Hannah More who observed Yearsley’s literary capability and arranged for her work to be published by subscription. Yearsley’s first collection, Poems on Several Occasions (1785) contained poems exploring themes of death, night, solitude, friendship and religion, and it brought her swift success. The collection includes ‘Clifton Hill’ written in January 1785, exactly a year after she was discovered destitute, and begins:

“In this lone hour, when angry storms descend,

And the chill’d soul deplores her distant friend;

When all her sprightly fires inactive lie,

And gloomy objects fill the mental eye;”

This poem references locations in and around Yearsley’s native Bristol, including the Hotwells, the River Avon, and the Clifton Church graveyard where her mother was recently buried. The speaker of ‘Clifton Hill’ then uses these places as the basis to describe working-class hardships.

The success of this collection was tainted. Hannah More kept control over Yearsley’s access to the proceeds which led to an acrimonious fallout. Yearsley retained greater control over future publications including Poems on Various Subjects (1787) and occasional poetic pieces over the next decade. An early abolitionist, she published her celebrated piece ‘A Poem on the Inhumanity of the Slave-Trade’ in 1788 as the campaign for the abolition of the slave trade was at its’ height. The main action of the poem takes place in an unspecified colonial location, but begins and ends in Bristol, both Yearsley’s birthplace and a focus of the slave trade:

“BRISTOL, thine heart hath throbb’d to glory. – Slaves,

E’en Christian slaves, have shook their chains, and gaz’d

With wonder and amazement on thee.”

The poem appeared relatively early in the poetic campaign against the slave trade. It depicts an enslaved African taking violent action against a British planter and invites the reader to sympathise with the African, a stance that would surely have shocked many contemporary readers.

Despite broadening her literary scope to write a novel and a play as well as further poetry, Yearsley sought further means of supporting herself financially. In 1793 she opened a circulating library in the Colonnade (see image below) situated in the well-appointed and fashionable location of Hotwells in Bristol. A catalogue exists of the books contained in the library with stringent rules regarding damage to borrowed books: “If any Book is wrote in, or the Leaf of a Book is torn or damaged, while in the Custody of a Subscriber, that Book, or if it should belong to a Set, that Set of Books to be paid for at the Price fixed in the Catalogue.”. The catalogue reveals a range of 666 books including history, travel, novels, plays and poetry, and fittingly ends with three volumes of Yearsley’s own poems. In common with other circulating libraries of the time, Yearsley’s library would have doubled as a stationer’s shop and also sold such items as medicines and perfumes.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Colonnade,_Hotwells,_Bristol.jpg

During this time she published a historical novel The Royal Captives in 1795 and a final volume of poems The Rural Lyre in 1796 before withdrawing from the literary scene. A beloved son died in 1799 followed by her husband in 1803. Ann Yearsley herself died at Melksham near Trowbridge, Wiltshire in May 1806, though her grave can be found in Birdcage Walk, Clifton.

Critical discussion of Yearsley’s writing has unsurprisingly been closely tied in with the events and circumstances of her life (as seen in Robert Southey’s 1831 biography) though modern critics are celebrated her achievements over gender and class discrimination, and are also giving her work, especially ‘A Poem on the Inhumanity of the Slave Trade’ the recognition it deserves.